How Local Environments Shape Long-Term Immunity and Chronic Inflammation

For decades, immunology was dominated by a circulation-centric model in which immune cells continuously migrate between blood, lymphoid organs, and peripheral tissues. In this framework, tissues were viewed as transient battlefields rather than long-term immune compartments. This paradigm has fundamentally shifted. Accumulating evidence now demonstrates that a substantial fraction of adaptive immunity is permanently embedded within tissues, where it acquires specialized functions shaped by the local microenvironment.

Among peripheral organs, the skin has emerged as a central model for understanding this form of localized immunity. Rather than acting solely as a physical barrier, the skin hosts large populations of tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) that persist independently of recirculating immune pools and play decisive roles in both protection and disease.

Tissue-resident memory T cells as a distinct immune lineage

Tissue-resident memory T cells arise following infection or inflammation and establish long-term residence within non-lymphoid tissues. Unlike central or effector memory T cells, TRM cells do not re-enter the circulation. Instead, they remain anchored within epithelial and stromal compartments, where they provide immediate immune surveillance.

In the skin, TRM cells localize preferentially to the epidermis and upper dermis. Their positioning is not random. It reflects active interactions with the tissue architecture, including epithelial cells, extracellular matrix components, and resident antigen-presenting cells. These interactions enforce a transcriptional and metabolic program that stabilizes residency and functional specialization.

Importantly, TRM cells express molecular signatures that actively prevent tissue egress, while simultaneously adapting their energy metabolism to the constraints of the local environment. This adaptation allows them to persist for years without continuous antigen exposure.

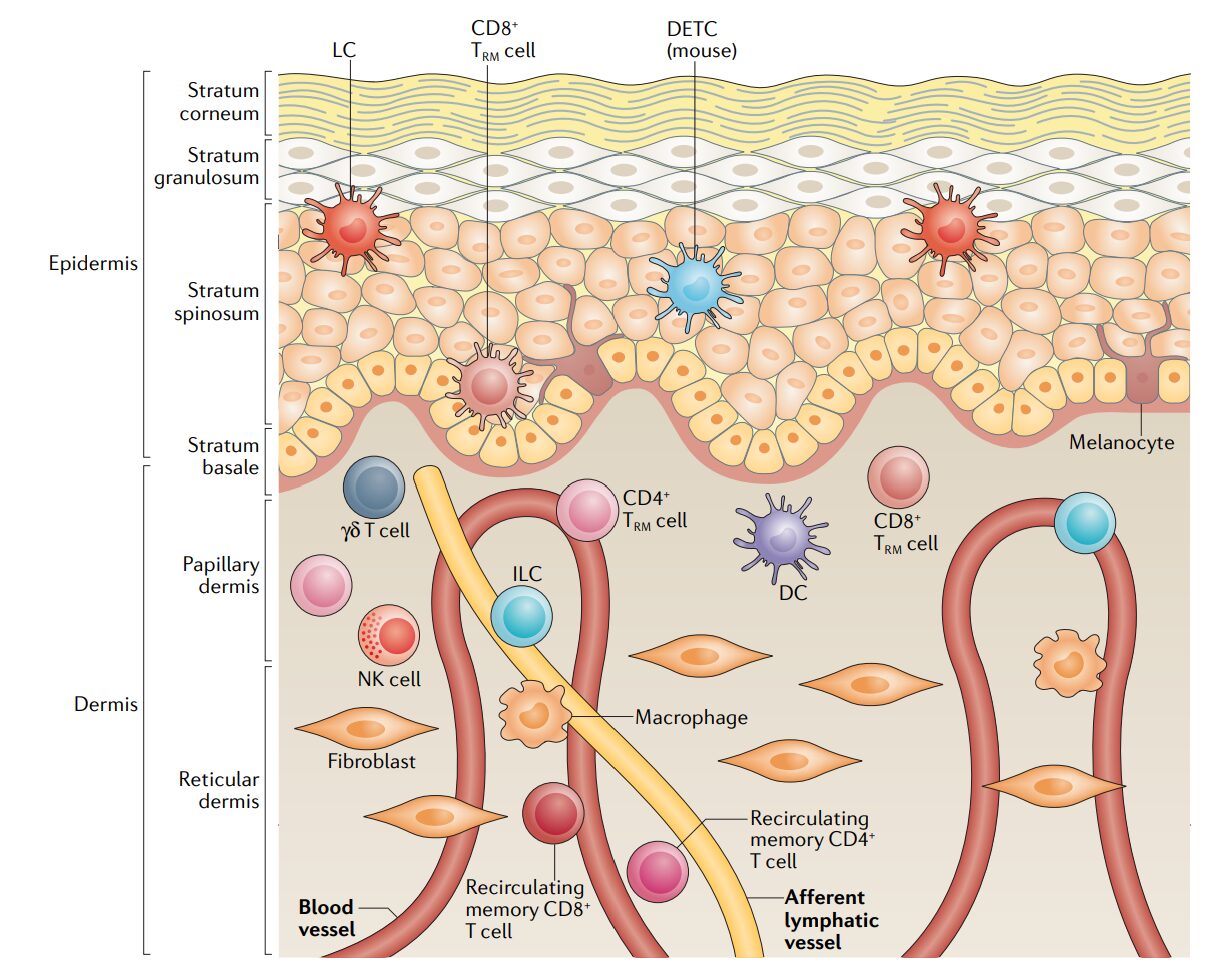

The spatial distribution of these resident immune cells within the skin illustrates how tissue architecture directly shapes immune function.

Figure – Spatial organization of immune cells in human skin.

The epidermis and dermis host distinct populations of immune cells, including tissue-resident memory T cells, dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells. Rather than circulating freely, many of these cells remain embedded within defined skin layers, where local structural, cellular, and metabolic cues regulate immune surveillance, rapid response, and long-term persistence.

Rapid protection through local immune memory

The strategic advantage of tissue residency lies in speed. TRM cells provide an immediate response upon pathogen re-encounter, bypassing the delays associated with immune cell recruitment from the blood. Upon activation, skin-resident T cells can rapidly produce effector cytokines, exert cytotoxic functions, and orchestrate broader immune responses within the surrounding tissue.

This localized immunity enhances host protection against recurrent infections at barrier sites. It also reshapes the classical notion of immune memory by demonstrating that effective recall responses do not require systemic mobilization.

However, this same efficiency introduces a new vulnerability.

Persistence as a driver of chronic inflammation

The long-term persistence of TRM cells becomes problematic in inflammatory skin diseases. In conditions such as psoriasis, vitiligo, and atopic dermatitis, pathogenic TRM populations remain embedded within clinically resolved lesions. Although inflammation subsides temporarily, these cells form a latent immunological imprint that predisposes the tissue to relapse.

This phenomenon explains why inflammatory lesions often recur at the same anatomical locations, even after apparently successful treatment. The tissue itself retains a memory of disease through its resident immune cells.

Crucially, conventional immunosuppressive therapies reduce inflammatory activity but do not eliminate TRM populations. As a result, disease control remains dependent on continuous treatment.

The tissue microenvironment as an active immune regulator

A key insight from the literature is that tissues are not passive containers for immune cells. The skin actively shapes immune behavior through biochemical, metabolic, and structural cues. Keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and resident myeloid cells provide signals that influence T cell survival, positioning, and functional polarization.

These signals extend beyond classical cytokine networks. Nutrient availability, lipid metabolism, oxygen tension, and spatial organization all contribute to immune cell programming. Over time, this local conditioning creates immune populations that are finely tuned to their tissue of residence.

Thus, immune function emerges from a continuous dialogue between cells and their environment, rather than from intrinsic cellular programming alone.

Rethinking immune exhaustion and persistence

The persistence of functional TRM cells challenges the assumption that prolonged immune activation inevitably leads to exhaustion. In tissue contexts, immune cells can maintain effector capacity without sustained antigen stimulation or chronic inflammatory signaling.

This observation suggests that immune dysfunction is not solely driven by molecular inhibitory pathways, but also by disruption of environmental compatibility. When immune cells are removed from their native tissue context or subjected to repeated perturbations, they may lose functional stability.

Therefore, immune exhaustion can be interpreted not only as a cell-intrinsic fate, but also as a failure of environmental support.

Therapeutic implications of tissue-resident immunity

Understanding tissue-resident immunity has profound therapeutic consequences. Targeting circulating immune cells alone is insufficient to achieve durable disease control in conditions driven by TRM populations. Effective intervention must address either the resident cells themselves or the tissue niches that sustain them.

Future strategies may involve reprogramming tissue environments, disrupting retention signals, or selectively modulating TRM function without compromising systemic immunity. Such approaches aim not merely to suppress symptoms, but to alter the underlying immunological memory embedded within tissues.

Conclusion

The discovery of tissue-resident memory T cells has transformed our understanding of immune organization. Immunity is not uniformly distributed throughout the body; it is spatially structured and deeply influenced by local environments.

In the skin, TRM cells exemplify how long-term immune protection and chronic inflammation arise from the same biological principle: persistent immune residency within tissues. Recognizing the tissue as an active immunological partner opens new perspectives on disease mechanisms, therapeutic design, and the future of immunomodulation.