Partial Reprogramming as a New Paradigm in Regenerative Medicine

For decades, regenerative medicine has largely relied on one central idea: if a cell is damaged, aged, or dysfunctional, it must be replaced. This logic has driven the development of stem cell therapies, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and cell transplantation strategies. While powerful, these approaches come with inherent limitations, including risks of tumorigenicity, loss of tissue-specific identity, and significant challenges in manufacturing and standardization.

A new conceptual shift is now emerging. Rather than replacing cells, researchers are beginning to repair their biological state. At the center of this shift lies partial epigenetic reprogramming, a strategy that aims to reverse cellular aging while preserving cellular identity. This approach challenges long-standing assumptions about irreversibility in cell fate and opens new directions for regenerative and translational biology.

Aging as an Epigenetic State, Not a One-Way Process

Cellular aging has traditionally been associated with cumulative damage: DNA mutations, telomere shortening, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein misfolding. While these processes undeniably contribute to aging, recent evidence suggests that epigenetic drift plays a central and potentially dominant role.

Epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, act as a regulatory layer that defines gene expression programs. Over time, these marks progressively deviate from their youthful configuration, leading to altered transcriptional profiles, reduced cellular function, and increased susceptibility to stress.

Crucially, epigenetic changes are inherently reversible. This observation laid the foundation for reprogramming technologies and ultimately for the discovery that cellular age itself may be reset independently of cell identity.

From Full Reprogramming to Partial Reprogramming

The discovery of iPSCs demonstrated that differentiated cells could be fully reprogrammed into a pluripotent state using a defined set of transcription factors. While transformative, full reprogramming effectively erases cellular identity, forcing cells back to an embryonic-like state. This reset comes at a cost: loss of tissue specificity, complex redifferentiation protocols, and elevated oncogenic risk.

Partial reprogramming takes a fundamentally different approach. Instead of driving cells all the way back to pluripotency, reprogramming factors are expressed transiently and in a tightly controlled manner. The objective is not to change what the cell is, but to restore how the cell functions.

Recent studies demonstrate that short-term expression of reprogramming factors can:

- Reverse age-associated gene expression patterns

- Reset epigenetic clocks toward a younger state

- Improve cellular resilience and function

- Preserve lineage-specific markers and morphology

This uncoupling of age reversal from dedifferentiation represents a conceptual breakthrough.

Preserving Identity While Restoring Youthful Function

One of the most striking findings from recent work is that partial reprogramming can rejuvenate cells without compromising their identity. Cells retain their transcriptional signatures, structural features, and functional markers, even as aging-associated pathways are reset.

This has profound implications, particularly for:

- Post-mitotic cells such as neurons

- Fragile or highly specialized cell types

- Tissues where cell replacement is impractical or risky

Rather than generating new cells to replace damaged ones, partial reprogramming suggests that existing cells can be repaired in situ, restoring function while maintaining tissue architecture.

Stability, Control, and the Importance of the Cellular Environment

While the biological concept of partial reprogramming is compelling, its translation depends critically on control. Reprogramming factors must be precisely dosed, temporally restricted, and applied in environments that preserve cellular integrity.

Cell state transitions are highly sensitive to:

- Mechanical stress

- Oxygen and nutrient gradients

- Homogeneity of culture conditions

- Shear forces and microenvironmental instability

Even subtle perturbations can push cells toward unwanted dedifferentiation, senescence, or stress responses. As a result, the physical and mechanical context of cell culture becomes a decisive variable, not a secondary technical detail.

This is particularly relevant when scaling experiments beyond small, static systems. Reproducibility, uniform exposure to stimuli, and preservation of fragile phenotypes are prerequisites for reliable rejuvenation strategies.

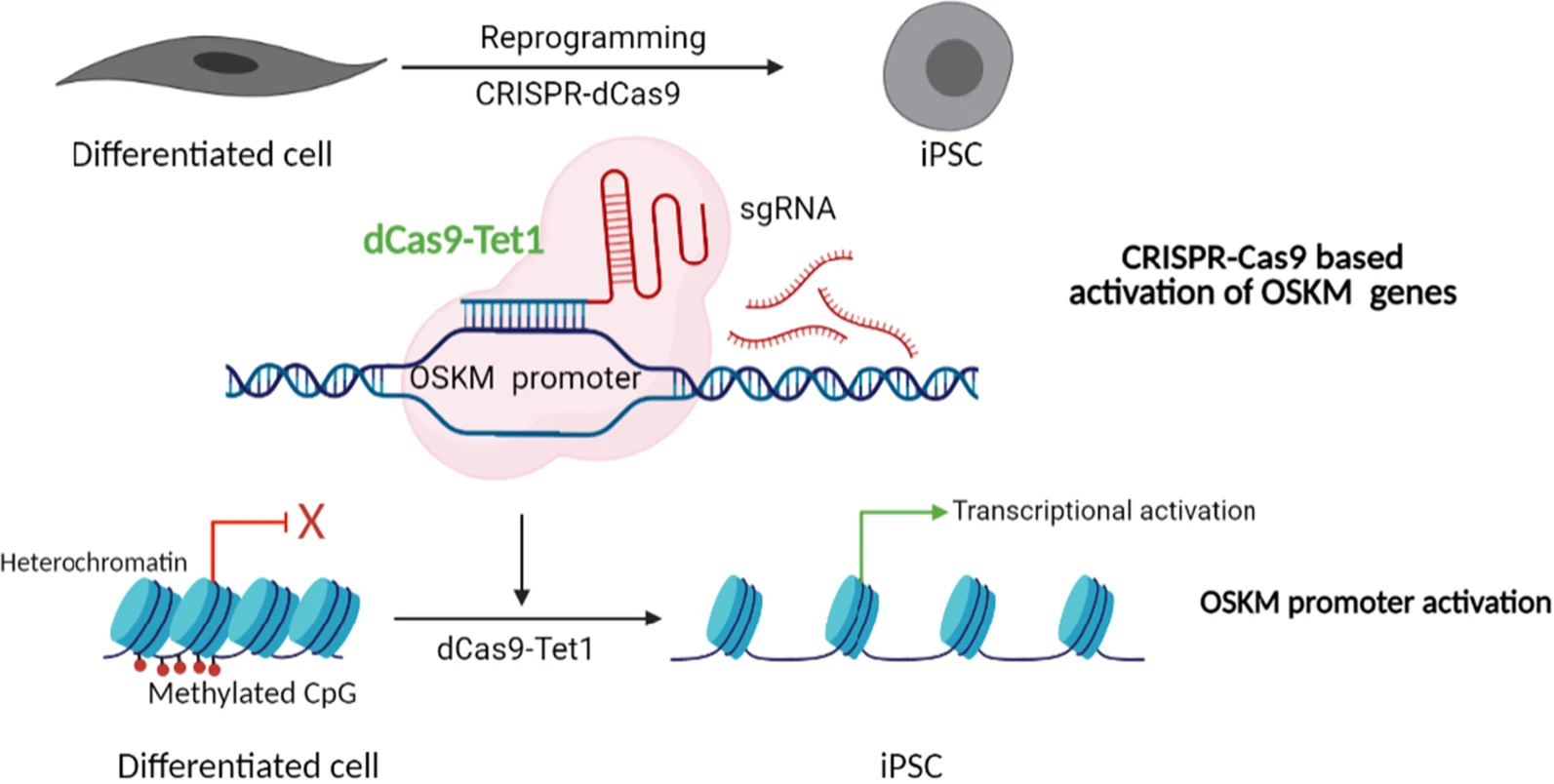

Mechanistic perspective on partial epigenetic reprogramming:

To clarify what partial epigenetic reprogramming means at the molecular level, the schematic below illustrates how cell identity and cellular age are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms rather than by irreversible genetic changes. This example highlights how targeted chromatin remodeling can restore transcriptional programs associated with a more youthful cellular state, without altering DNA sequence or forcing full dedifferentiation.

Fig. 1. Conceptual illustration of epigenetic reprogramming enabling cellular state rejuvenation without loss of identity.

Adapted from “Epigenetic reprogramming of cell identity: lessons from development for regenerative medicine”, Basu A. and Tiwari V.K., 2021.

In differentiated cells, key developmental gene networks are epigenetically silenced through chromatin compaction and DNA methylation. This epigenetic configuration stabilizes cell identity but also limits cellular plasticity and contributes to functional decline during aging.

The schematic illustrates how partial reprogramming operates by selectively relieving epigenetic constraints. By restoring chromatin accessibility at specific regulatory regions, transcriptional activity can be reactivated without modifying the underlying genetic code. Importantly, this process does not necessarily drive cells toward full pluripotency, but rather shifts them toward a more functional and resilient state while preserving lineage identity.

This mechanistic view reinforces a central message of partial reprogramming strategies: successful cellular rejuvenation depends not only on molecular interventions, but on the ability to maintain stable, well-controlled cellular environments that support safe and reproducible epigenetic remodeling.

Implications for Regenerative Medicine and Advanced Therapies

Partial reprogramming reframes regenerative medicine around state correction rather than cell replacement. Potential applications span multiple domains:

- Neurodegenerative disorders, where replacing neurons is not feasible

- Musculoskeletal aging, where functional restoration may suffice

- Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases linked to cellular senescence

- Age-related decline in stem and progenitor cell populations

In each case, the challenge is not merely biological feasibility, but process reliability. Therapies based on partial reprogramming will require culture systems capable of maintaining stable, low-stress conditions over time, ensuring that rejuvenation is consistent, controlled, and safe.

Toward a New Definition of Regeneration

Partial epigenetic reprogramming suggests that regeneration does not always require rebuilding tissues from scratch. Instead, it may be possible to reset the internal state of cells, restoring youthful function while respecting biological identity.

This emerging paradigm places new emphasis on:

- Precision control of cell environments

- Integration of biology with biophysics

- Scalable, reproducible 3D culture systems

- Technologies that protect fragile cell states rather than disrupt them

As regenerative medicine moves forward, success will depend not only on molecular tools, but on how cells are cultured, maintained, and protected during state transitions.

The future of regeneration may lie less in creating new cells, and more in teaching existing cells how to be young again without forgetting who they are.