Why Perfect Knowledge Does Not Guarantee Accurate Forecasts

Prediction has long been considered a cornerstone of scientific understanding. In many fields, the ability to forecast future behavior is implicitly treated as proof that the underlying system has been properly understood. When predictions fail, the explanation is usually sought in insufficient data, experimental noise, or incomplete models. According to this view, improving measurements and refining theoretical frameworks should progressively eliminate uncertainty.

However, research on complex systems reveals a more fundamental limitation. Certain systems remain intrinsically unpredictable, even when their governing rules are deterministic and fully specified. This unpredictability does not arise from randomness or ignorance, but from the internal structure of the system itself. Living matter frequently operates within this regime.

Understanding the limits of predictability therefore requires moving beyond the traditional assumption that better data necessarily lead to better forecasts.

Beyond the Opposition Between Order and Randomness

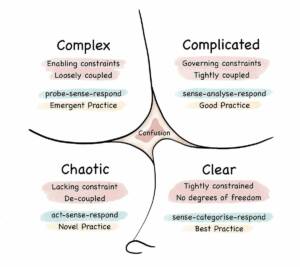

Classical intuition often places natural systems along a simple continuum. At one extreme lie perfectly ordered systems that are fully predictable. At the other extreme lie random systems that are unpredictable because they lack structure. This opposition is misleading.

Perfectly ordered systems are indeed predictable, but they generate little informational richness. Completely random systems are unpredictable, but also devoid of meaningful organization. Complexity emerges between these two extremes. In this intermediate regime, systems produce structured patterns that cannot be reduced to simple predictive rules.

Many natural and biological systems operate precisely in this region. Their behavior is organized and reproducible in the short term, yet resistant to long term simplification. Structure and unpredictability coexist.

Figure. Conceptual framework distinguishing ordered, complicated, complex, and chaotic regimes. Complex systems occupy an intermediate space where structured behavior emerges without full predictability, illustrating why forecasting in living systems is fundamentally limited.

Deterministic Chaos and Sensitivity to Initial Conditions

One of the most important sources of intrinsic unpredictability is deterministic chaos. Chaotic systems evolve according to precise and deterministic rules, yet they exhibit extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. Infinitesimal differences at the starting point grow over time until trajectories diverge completely.

This sensitivity imposes a strict horizon on prediction. Beyond a certain time scale, even perfect knowledge of the initial state becomes insufficient to determine future behavior. The loss of predictability is not caused by noise, but by the amplification of uncertainty inherent in the dynamics.

In living systems, similar sensitivities can arise from nonlinear interactions, regulatory networks, feedback loops, and collective processes. As a result, biological trajectories that start from nearly identical states may evolve in markedly different ways.

Weak Chaos and the Illusion of Stability

Strong chaos is not required for predictability to fail. Some systems exhibit weak chaos, characterized by a slow divergence of trajectories. These systems may appear stable and predictable over extended periods, before unpredictability gradually emerges.

This phenomenon creates an illusion of control. Short term reproducibility can coexist with long term unpredictability. A system may follow expected patterns for a significant duration while remaining fundamentally unpredictable beyond a certain temporal horizon.

Such behavior is particularly relevant in biological contexts, where apparent stability often masks deeper dynamical instability.

Structured Dynamics Without Predictive Compression

A central insight from complexity theory is that structure does not necessarily imply simplification. Some systems generate rich and organized patterns that cannot be compressed into reduced predictive models.

In these cases, the only way to determine future behavior is to explicitly simulate the system step by step. No shortcut exists that allows the future to be inferred without reproducing the underlying dynamics in full. Prediction becomes equivalent to computation.

This establishes a fundamental limit. Improvements in data quality or computational power do not overcome this barrier. The limitation is inherent to the structure of the system.

Information Storage and Hidden Causal Architecture

Complex systems do not merely generate information. They store information about their past and use it to shape future behavior. Predictability therefore depends on how information is internally organized and propagated through time.

In many systems, relevant information is distributed across multiple scales and encoded in transient correlations rather than stable variables. The causal architecture governing the dynamics is partially hidden and continuously evolving.

Living systems exemplify this challenge. Their behavior reflects a history dependent organization that resists static descriptions and limits the effectiveness of state based predictive models.

Multiscale Coupling and Predictive Boundaries

Another fundamental obstacle to prediction arises from multiscale coupling. Processes operating at different temporal and spatial scales interact continuously. No single level of description captures the full dynamics.

Predictability may exist at one scale while failing at another. Regular behavior at a macroscopic level can coexist with unpredictability at finer scales. Causal influence does not flow in a single direction.

Living matter is intrinsically multiscale. This entanglement places unavoidable constraints on global prediction.

Implications for the Study of Living Matter

The recognition that unpredictability can be intrinsic to system dynamics challenges a deeply rooted assumption in biology. Even with ideal data and perfect knowledge of governing rules, certain aspects of living systems remain fundamentally unpredictable.

This does not diminish scientific understanding. Instead, it reframes its objectives. The goal is not to eliminate uncertainty, but to identify the boundaries within which prediction is meaningful. Understanding these limits allows for more realistic interpretations of variability, robustness, and adaptability in living systems.

Conclusion

The boundary between order and chaos is not a simple dividing line. It is a region where structure and unpredictability coexist. Research on complex systems shows that unpredictability can arise from deterministic dynamics and organized structure, rather than from randomness.

For living matter, this insight is essential. It reveals that uncertainty is not merely a consequence of experimental limitations, but a fundamental property of complex biological systems. Accepting the limits of predictability is therefore a necessary step toward a deeper and more accurate understanding of life as a physical process.