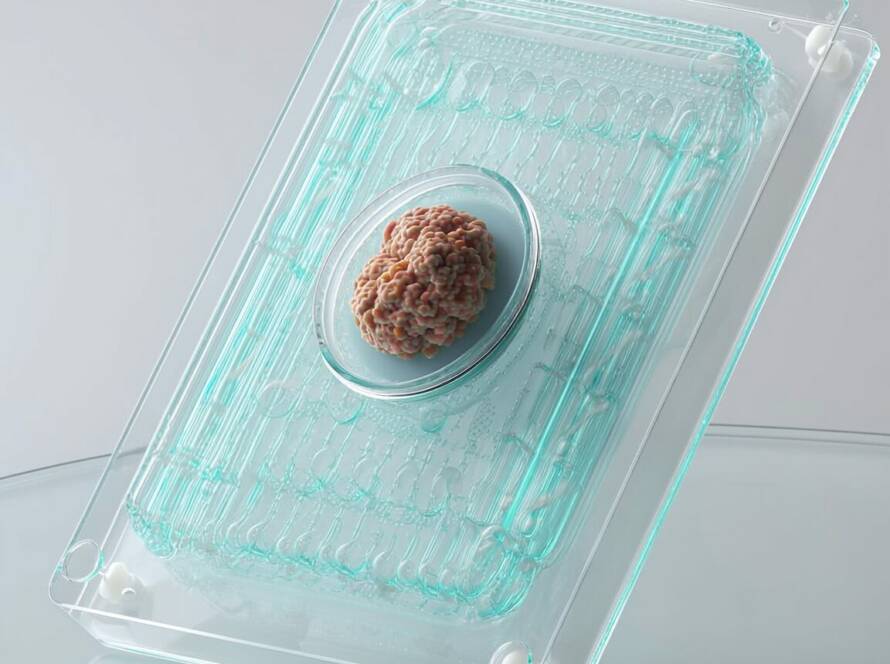

Over the past decade, organoids have emerged as one of the most powerful experimental systems in modern biology. By enabling pluripotent and adult stem cells to self-organize into tissue-like structures, organoids have transformed our ability to model human development, disease progression, and drug responses in vitro. Yet despite their conceptual elegance, most organoid systems remain constrained by a fundamental biophysical limitation: the diffusion ceiling around 400 micrometers.

Beyond this size, passive diffusion of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolites becomes insufficient. As a result, hypoxic cores form, metabolic waste accumulates, and cellular stress progressively undermines tissue integrity. This diffusion barrier does not simply limit organoid size; it restricts long-term viability, functional maturation, and physiological relevance. Consequently, the next major leap in organoid biology is not incremental optimization, but a conceptual shift toward vascularized, perfusable, and metabolically stable organoids.

From diffusion-limited structures to perfusable living systems

In vivo, no tissue exceeding a few hundred micrometers survives without a vascular network. Blood vessels are not only conduits for oxygen and nutrients; they actively shape tissue patterning, metabolism, and functional specialization. Organoids, by contrast, have historically relied on static or mildly agitated culture systems, implicitly assuming that biochemical signals alone would drive maturation.

This assumption has been fundamentally challenged by pioneering work from Takanori Takebe and collaborators, who demonstrated that vascularization can emerge intrinsically within organoids. By co-culturing pluripotent stem cell–derived progenitors with endothelial and mesenchymal populations, their studies showed that organoids can spontaneously form internal vascular networks capable of functional perfusion and integration after transplantation.

These findings reframed vascularization not as an external engineering add-on, but as an emergent biological property, provided the physical environment allows multicellular coordination to unfold.

Mechanical permissiveness as a prerequisite for vascular self-organization

While biochemical signaling remains essential, recent evidence increasingly points to mechanical conditions as the dominant determinant of successful vascularization. Endothelial cells are exceptionally sensitive to hydrodynamic forces. Excessive shear stress disrupts sprouting, destabilizes nascent lumens, and causes premature collapse of fragile vascular structures. Conversely, overly static environments often promote uncontrolled aggregation, leading to disorganized cellular masses rather than structured tissues.

What emerges from post-vascular organoid research is the existence of a narrow mechanical window in which vascular self-organization becomes possible. This window is defined by low, uniform shear forces and stable three-dimensional suspension, allowing endothelial cells to coordinate collective behaviors rather than responding to stochastic mechanical perturbations.

At this stage, it is useful to summarize the core physical requirements identified across multiple studies:

preservation of low shear stress to avoid endothelial damage,

homogeneous mass transfer to prevent localized hypoxia or nutrient depletion,

mechanical stability over time to support vessel maturation and remodeling.

Outside of these conditions, even the most sophisticated differentiation protocols fail to produce functional vascular networks.

Endothelial network maturation and metabolic patterning

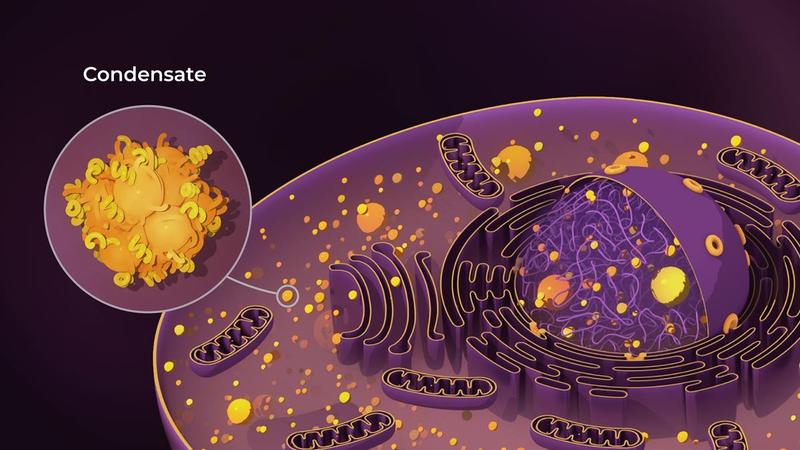

High-resolution imaging and single-cell transcriptomic analyses published in Nature Biotechnology and Cell Stem Cell reveal that endothelial cells within organoids follow a developmental trajectory closely resembling embryonic vasculogenesis. Tip cell selection, lumen formation, and network pruning occur autonomously, without predefined scaffolds. Crucially, this process depends on minimizing mechanical noise within the culture environment.

Once established, vascular networks unlock a second level of complexity: metabolic zonation. Rather than eliminating gradients entirely, vascularized organoids develop controlled spatial variations in oxygen and nutrient availability. These gradients are not pathological; they are functional. They mirror native tissue organization, such as hepatic zonation or regional specialization in neural tissues, enabling higher-order physiological behaviors.

This metabolic structuring is impossible in diffusion-limited organoids and is actively disrupted in high-shear systems. In contrast, low-shear homogeneous environments allow metabolism itself to become an organizing signal, rather than a limiting factor.

Why physical culture design has become the main bottleneck

As stem cell sources, differentiation protocols, and genetic tools continue to mature, the primary limitation in advanced organoid systems has shifted. The challenge is no longer how to specify cell identity, but how to preserve fragile multicellular architectures over time.

Across the literature, a consistent conclusion emerges: post-vascular organoid success is constrained more by biophysical incompatibility than by missing molecular cues. Culture systems that fail to control shear stress and mixing homogeneity inadvertently destroy the very structures they aim to generate.

In this context, one final synthesis can be made:

vascularization is biologically programmed,

but its expression is mechanically gated.

Conclusion

Crossing the 400 µm barrier is not about scaling organoids in size; it is about enabling them to function as living, perfusable systems. Post-vascular organoids represent a transition from static 3D aggregates to dynamically organized tissues, capable of sustaining metabolic complexity and long-term viability.

As organoid research moves toward translational, industrial, and clinical applications, mastering the mechanical dimension of 3D culture will be as decisive as mastering genetics or biochemistry. The future of organoids lies precisely at this intersection, where biology, physics, and engineering converge.